By Scott Kaar, M.D.

A metacarpal fracture is a fracture (break) of the tubular bones within the palm (metacarpals). They classically occur in the small finger metacarpal bone in boxers or athletes of other sports or activities. This type of fracture has therefore become to be known as a “boxer’s fracture.” Each of the digits of the hand has a corresponding metacarpal bone associated with it, and any of these metacarpals may be fractured during a high energy impact to an athlete’s hand.

These injuries are also common in other sports besides boxing. For example Ronnie Brown of the Miami Dolphins and Tony Romo of the Dallas Cowboys each spent time on the IR from suffering a metacarpal fracture as did the Mavericks Jason Terry who had surgery to fix his metacarpal fracture.

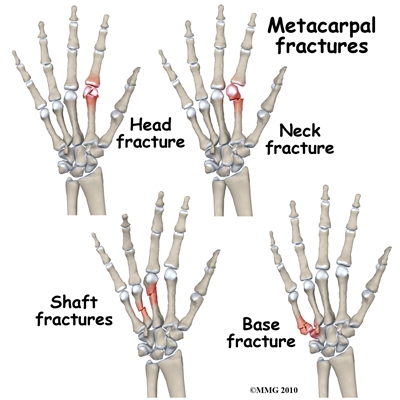

Anatomy of metacarpal

The metacarpals are the tubular bones that comprise most of the space in the palm. Each of the fingers (digits) has a corresponding metacarpal that links the wrist bones to the phalanges (individual bones of the fingers).

There are flexor tendons on the palm side of the metacarpals that act to flex, or bend the fingers as in making a fist. There are extensor tendons on the back of the hand that act to extend, or straighten the fingers. In between the metacarpal bones are the small intrinsic muscles (the interosseous and lumbrical muscles) that further help to control fine finger motion. When a metacarpal fracture happens, the finger flexors and the intrinsic muscles act together to bend the fracture toward the palm (apex dorsal angulation). How much the fracture bends is somewhat dependant on how much force caused the injury in the first place. A higher force injury can lead to more bending (displacement of the fracture).

In an athlete’s normal uninjured hand, there is less motion at the joints of the index and long finger and more motion at the ring and small fingers. The increased motion at the two smaller fingers allows for more angulation to be acceptable as the fracture heals. This is because the increased normal motion of these two metacarpal bones can allow the hand to adapt to any permanent deformity. On the other hand, the index and long fingers’ have lesser ability to adapt to metacarpal fracture bending because they have less natural motion. The normal motion of the metacarpals can be seen when one makes a tight fist while watching the ring and small finger side of the back of the hand bend further inward.

Diagnosis

An injured athlete will describe a forceful blow to the hand. It will often be due to a punching injury or a direct blow from a fall or crush injury. Their hand will be very painful, maximally so over the specific metacarpal bone that is fractured. There will be swelling, often a considerable amount, as well as bruising directly over the injury. They may have difficulty moving the fingers due to the amount of pain from the fracture.

On physical examination, the athlete’s hand will be most tender over the injured metacarpal. There may be palpable fracture ends of the bone which can be felt to move if pressed. If the fracture becomes angled, then the hand may be bent inwards towards the palm some and there may be a point felt from the apex of the fracture. One important aspect of the physical exam is whether there is a rotational deformity of the fracture. This can be assessed by asking the patient to make a fist. When they do so, the fingers should all line up properly and be parallel. If the finger corresponding to the fractured metacarpal does not line up properly with the surrounding fingers, then the fracture ends are most likely rotated. When this happens, often the injured finger will scissor under or above an adjacent finger.

A metacarpal fracture can occur in any sport although the highest risk is in those sports where there is a risk of a high energy impact occurring to the athlete’s hand. Classically this occurs in boxers and other athletes involved in the martial arts. However other impact sports like football and rugby place the competitor’s hands at risk of impact against things like opposing players’ helmets and pads as well as the ground itself.

A metacarpal fracture occurs when the hand strikes another object with sufficient force to cause the metacarpal bones to break. This commonly occurs during a punch with a clenched fist. In doing so, the knuckles (the heads of the metacarpals) strike directly against a hard object and all the force of the blow is transmitted directly through the metacarpals. This explains why boxers are susceptible to these fractures, especially when someone throws a punch without the protection of gloves. A crush injury to the hand can also cause a metacarpal fracture such as if someone lands directly on the athlete’s hand.

Treatment

Initial treatment – metacarpal fracture splint

Initial treatment involves using a metacarpal fracture splint on the hand. In doing so, the hard splint does not circumferentially surround the hand and forearm, rather some of circumference is only a soft wrap to allow for swelling to occur. The finger tips will be usually out of the splint and left free to allow them some motion and to not get stiff.

Subsequently treated

After a closer exam and radiographs are performed, the next decision is whether or not surgery is necessary. In the great majority of cases, the fracture is lined up sufficiently and there is not too much deformity of the bone ends. More deformity can be accepted in the ring and small finger without needing surgery because these fingers have a greater compensatory capability because they have more motion than the index and long fingers. Any significant scissoring is unacceptable to be treated closed as this deformity is poorly tolerated even after the fracture heals.

If the metacarpal fracture is indeed lined up within an acceptable range, then the patient’s metacarpal fracture splint is changed to a hard circumferential cast in many cases. In some cases where the fracture is not displaced (shifted) at all or very little, a removable splint can be considered, however the athlete accepts a risk of the fracture bone ends shifting further especially if the hand is impacted a second time. In most cases, the metacarpal fracture heals well and does so over the course of 6 to 8 weeks. Over that time the cast can be removed after a period of time and changed to a removable splint. X-rays are checked every few weeks to be sure the fracture is healing properly and the bone ends maintain their alignment.

When to See the Doctor

Hundreds of athletes sustain acute injuries everyday, which can be treated safely at home using the P.R.I.C.E. principle. But if there are signs or symptoms of a serious injury, emergency first aid should be provided while keeping the athlete calm and still until emergency service personnel arrive. Signs of an emergency situation when you should seek care and doctor treatment can include:

- Bone or joint that is clearly deformed or broken

- Severe swelling and/or pain,

- Unsteady breathing or pulse

- Disorientation or confusion

- Paralysis, tingling, or numbness

In addition, an athlete should seek medical care if acute symptoms do not go away after rest and home treatment using the P.R.I.C.E principle.

What imaging is necessary for a metacarpal fracture?

Definitive diagnosis of a metacarpal fracture requires a series of hand radiographs to clearly evaluate the hand bones including the metacarpals. In certain cases where the fracture needs to be seen in greater detail, a CT scan can be considered, but this is highly unusual. Other imaging tests like an MRI are almost never needed for an isolated metacarpal fracture as they normally don’t add any further information beyond a regular x-ray. If other injuries are suspected, but not seen clearly on the x-rays, then further tests could be considered.

Is metacarpal fracture surgery needed?

Operative stabilization is necessary for metacarpal fractures where there is too much bending (angulation) or displacement at the fracture site. Normally around 15° is the maximum amount of angulation tolerated in the index and long finger metacarpals, while 35° is acceptable for the ring finger, and 50° is often tolerated in the small finger. Also, if scissoring is present indicating unacceptable rotation of the fracture ends, then fixation should be considered. Sometimes an attempt at realigning the fracture (closed reduction) is possible without an incision. If successful, the patient can be treated in a cast as outlined above.

Other less common reasons for surgery include a fracture where the overlying skin is broken and the wound communicates with the fractured bones (open fracture). In this case, surgery is often required to clean out the wound to decrease the chance of an infection. In those injuries, the fractured metacarpal may be unstable because the soft-tissue surrounding the bones is often worse injured and therefore provides less stability to the fracture. Lastly, in rare cases there may be a tendon laceration that occurs at the same time as the metacarpal fracture. In these injuries, the fracture is often fixed at the same time as the tendon is repaired.

Metacarpal fracture surgery

An injured athlete with a metacarpal fracture that requires operative stabilization is taken to the operating room and either sedated or placed under general anesthesia to relax the patient and allow the fracture to be manipulated. Sometimes the fracture ends can be realigned and pinned without a large incision. Many times however an incision is needed and direct visualization of the fracture ends is achieved. The fracture is realigned (reduced) under direct visualization and then fixed in place with pins, screws or plates and screws (open reduction internal fixation). Then the fracture is immobilized for a period of time to protect the incision and the fracture.

Recovery time for metacarpal fracture

Following a metacarpal fracture treated operatively or non-operatively, the patient’s hand and wrist are immobilized in a splint, cast or sometimes a removable splint as it heals. Radiographs are taken periodically to be sure that the fracture maintains its proper alignment and continues to heal. Metacarpal fractures usually take few months to heal, but the exact timing of an athlete’s return to their sport depends on how stable the fracture is and how much risk of re-displacing the fracture, the athlete, and treating physician feels comfortable with. In some sports, the athlete can train or compete even with a cast on such as running while others like swimming are virtually impossible to participate in until a splint or cast is no longer worn. Sometimes in collision sports like football, an athlete can compete with a protective removable splint while the fracture continues to heal although this is usually only possible for certain positions like lineman and defenders because they don’t rely as much on holding onto the ball.

References

- Geissler WB. Operative fixation of metacarpal and phalangeal fractures in athletes. Hand Clin. 2009 Aug;25(3):409-21.

- Henry MH. Fractures of the proximal phalanx and metacarpals in the hand: preferred methods of stabilization. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008 Oct;16(10):586-95.

- Singletary S, Freeland AE, Jarrett CA. Metacarpal fractures in athletes: treatment, rehabilitation, and safe early return to play. J Hand Ther. 2003 Apr-Jun;16(2):171-9.